Tongues of Fire: A Biblical and Modern Exploration of Glossolalia

Few topics in Christianity generate as much curiosity, debate, and confusion as “speaking in tongues.” For some, it is a vital prayer language that connects the human spirit to the divine. For others, it is a historical footnote that ceased centuries ago.

And for many observing modern religious media, it is a puzzling phenomenon where preachers switch rapidly between intelligible speech and unknown utterances.To understand this phenomenon, we must look at where it started, the rules set down for its use, and how it has evolved into a cultural signal in the modern church.

1. Defining the Phenomenon

In biblical studies, “speaking in tongues” is generally categorized into two distinct types:

Xenolalia (Acts 2): The miraculous ability to speak a known human language that the speaker has never learned. This occurred at Pentecost so that the crowd could hear the Gospel in their native dialects.

Glossolalia (1 Corinthians): Ecstatic speech or a “prayer language” that is unintelligible to the speaker and the listener. This is viewed as communication directed from the human spirit to God, bypassing the mind.

2. The Biblical Foundation (The “Then”)

The New Testament presents two primary contexts for tongues: Public Sign and Private Devotion.

The Historical Narrative: Acts

In the book of Acts, tongues serve as “proof” of God’s movement.

Pentecost (Acts 2):

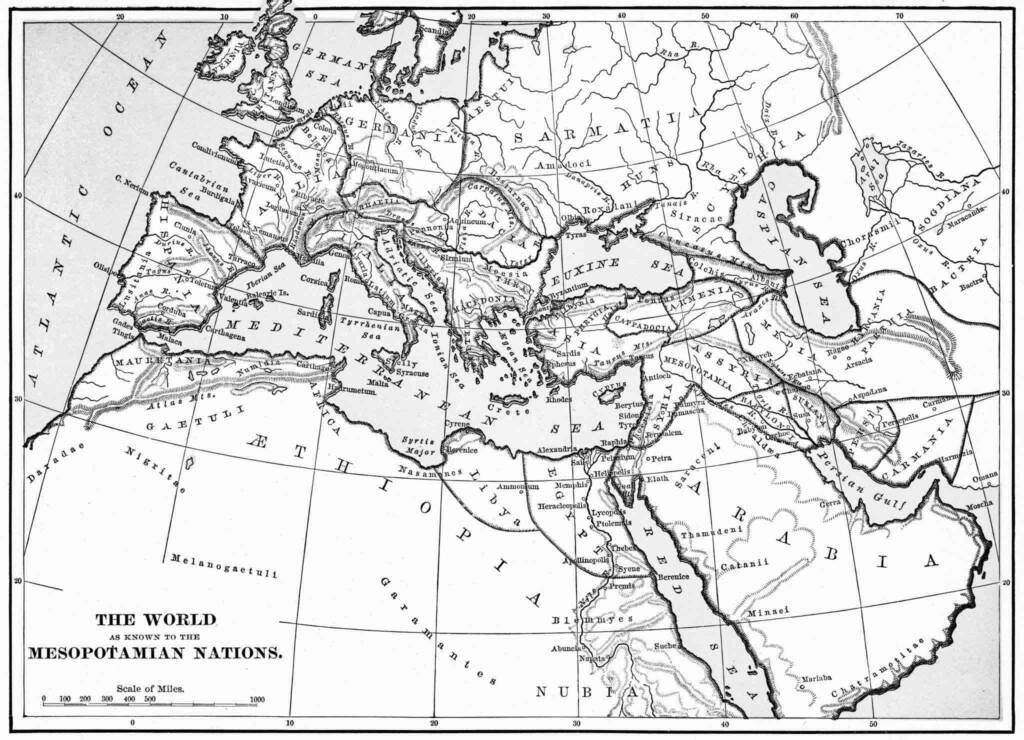

The Holy Spirit descends on the disciples. They speak in the languages of the Parthians, Medes, and others. The purpose here was missional—breaking language barriers to spread the Gospel.

The Gentile Shift (Acts 10): When Peter preached to Cornelius (a Roman centurion), the Holy Spirit fell on the Gentiles, and they spoke in tongues. This was crucial evidence for the Jewish Christians that God had accepted non-Jews into the faith.

The Instructional Teaching: 1 Corinthians 12–14

Years later, the Apostle Paul wrote to the church in Corinth to correct the misuse of this gift. The Corinthians were using tongues chaotically in their services. Paul established a hierarchy of gifts:

Prophecy is preferred in church because it is intelligible and edifies (builds up) the whole group.

Tongues are for self-edification. Paul says, “He who speaks in a tongue edifies himself” (1 Cor 14:4).

3. Paul’s “Rules of Engagement”

This section is critical for understanding the tension in modern usage. In 1 Corinthians 14, Paul lays down strict guidelines for public worship that are often cited by critics of modern practice:

The Requirement of Interpretation: “If any speak in a tongue… let one interpret. But if there is no interpreter, let him keep silent in church” (v. 27-28).

The “Five Word” Rule: “In the church I would rather speak five words with my understanding… than ten thousand words in a tongue” (v. 19).

Decency and Order: The service should not be chaotic or confusing to outsiders.

4. Modern Usage and Cultural Observation (The “Now”)

Today, the practice of tongues has evolved beyond a simple theological debate into a cultural identifier within Evangelical and Charismatic Christianity.

A. The “Initial Evidence” Doctrine

In classical Pentecostal denominations (like the Assemblies of God), speaking in tongues is viewed as the “Initial Physical Evidence” of the Baptism in the Holy Spirit. It is a rite of passage for believers and a requirement for clergy in many denominations.

B. The “Rhetorical” Use in Preaching

As noted by modern observers of religious media (YouTube, TV evangelism), there is a prevalent use of tongues that falls outside the strict biblical categories of “prayer” or “missionary work.”

Frequently, preachers, worship leaders, or interviewees will insert brief moments of tongues into English sentences.

Example: “God is moving in this place… [brief phrase in tongues]… and He wants to heal you.”

The Context: This is often preceded by statements like “I feel the Holy Spirit” or “The anointing is heavy.”

Why do they do this? Sociologists and insiders suggest this functions as a Spiritual Signal:

Authentication: It validates the speaker’s spiritual authority. It signals to the audience, “I am not just giving a speech; I am channeling a divine message.”

Emphasis: It acts as a spiritual exclamation point, heightening the emotional intensity of the sermon.

Tribal Marker: It instantly identifies the speaker as “one of us” to a Charismatic audience.

The Controversy: Critics argue this violates Paul’s instruction in 1 Corinthians 14, as these “sermon interruptions” are rarely interpreted. However, proponents view it as an involuntary “overflow” of the Spirit that cannot be contained by homiletic rules.

5. Scientific and Linguistic Perspectives

It is worth noting that scientific study has approached glossolalia from a different angle.

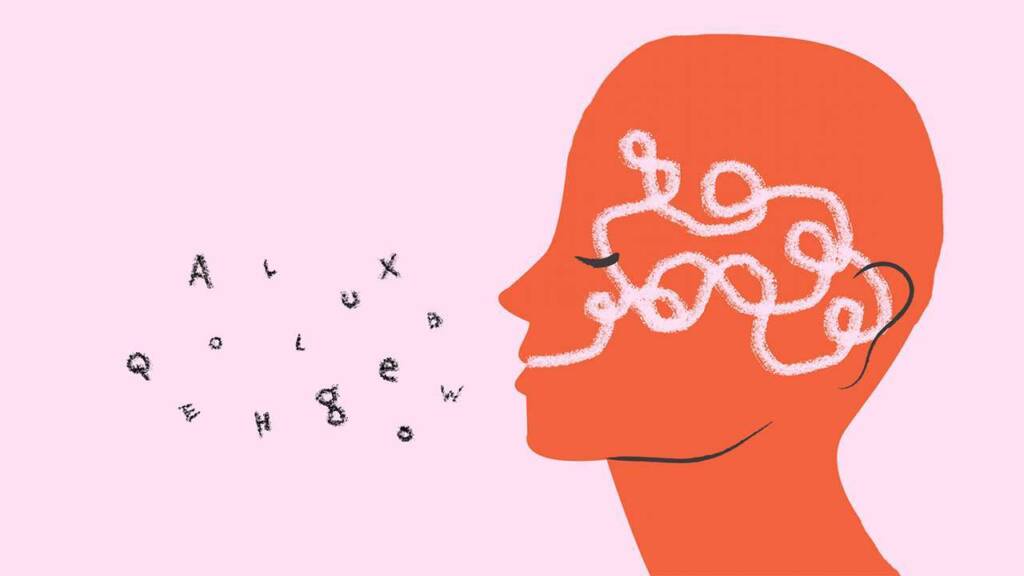

Linguistics: Researchers generally agree that modern glossolalia lacks the syntax and structure of human language. It relies on the phonemes (sounds) of the speaker’s native language but rearranges them.

Neuroscience: Brain scans of people speaking in tongues show decreased activity in the frontal lobes (the control center of the brain) and increased activity in the parietal lobes. This supports the practitioner’s claim that they are not “consciously controlling” the speech, but rather surrendering control.

6. Conclusion

The phenomenon of speaking in tongues remains one of the most distinct features of the Christian faith. From its explosive debut in Acts as a tool for evangelism to its modern role as a personal prayer language and a pulpit signal of “anointing,” it continues to evolve.

Whether one views it as a miraculous gift that requires strict biblical order, or a psychological release that deepens spiritual connection, it forces every believer to grapple with the mystery of how the divine interacts with the human mind.

The Song: Whispers of Fire

“Whispers of Fire” is a poetic worship anthem inspired by Pentecost, where the apostles received tongues of fire to proclaim the gospel of Christ. Blending mystical imagery, ancient echoes like “Sanctus,” and a reverent invocation of Adonai, the song captures the wonder of praying in the Spirit and the holy purpose behind the gift of tongues. Epic, emotional, and deeply devotional, it invites listeners into the same flame-lit surrender that ignited the Church.

[Verse 1 — Pentecost + Purpose]

When the Breath of God descended

on the waiting hearts that day,

flames like crowns on chosen foreheads

glowed and would not fade away.

Apostles trembling in the wonder,

speech awakened by the flame—

for the Spirit lit their voices

to proclaim the gospel of Christ by name.

[Chorus]

Whispers of fire, rising higher,

songs the mortal tongue can’t frame.

Rivers hidden, overflowed,

syllables the heart proclaimed.

O Spirit, shape my yearning voice,

let mystery become my choice—

till every tear and holy sound

is heaven touching earthly ground.

[Verse 2]

In the stillness of surrender

when my words begin to fall,

tongues of longing break like waters

echoing Your ancient call.

Groans that shimmer without meaning,

yet they pierce the veil above—

for the Spirit knows the language

of unutterable love.

[Bridge — With Sanctus + Adonai]

Let the Upper Room awaken

in the chambers of my soul;

let the winds of new beginnings

find the places once left cold.

Every trembling note surrendered,

every breath a sacred sign—

till my whisper turns to worship:

“Adonai… Sanctus… Your fire becomes mine.”

[Final Chorus – Soaring]

Whispers of fire, rising higher,

lift my worship, break me free.

Speak the language of the Kingdom

through the dust that forms of me.

Spirit, kindle every sound,

wrap me in Your holy flame—

till the breath within my chest

only lives to praise Your Name.